Road Trip: Journey to the Arctic Ocean in the 2025 Toyota 4Runner

On the road to the Arctic Ocean, we found beauty, resilience, and community

Article content

For the past 10 years, our journey has been guiding us toward the north.

My daughter and I have spent the last decade’s worth of summers road tripping across Canada. Our mission: collect every souvenir medallion from Parks Canada’s Xplorers program. Through educational activities, this program encourages kids and their families to discover Canada’s national parks and national historic sites from coast to coast.

After traveling through all 10 provinces and a territory, we started this summer with just seven sites left to visit. But these final sites are some of the most difficult to reach: Fort St. James National Historic Site in northern British Columbia; Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site on Haida Gwaii; Kluane National Park and Reserve and three national historic sites in the Yukon; and Pingo Canadian Landmark, located just outside Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

Since we first set out to visit the more than 100 sites in the program, I’ve known this trip was inevitable. I intentionally left it for last because I knew it would be our most challenging. I felt it was important that my daughter be old enough to understand this and actively opt in — and, in a dire emergency, to get herself to safety if needed.

I also knew this trip would push me well outside my comfort zone. I’ve been on some pretty wild adventures, but I’m really a very risk-averse person at my core. While I estimate I’ve logged more than 100,000 kilometres of driving across Canada over this last decade, there are a few things I suspected this trip would ask of me that I’d never done before, like using a gas can and changing a tire on my own. (We live in the city. This is what CAA is for, right?)

The returns, though, would be great. We’d already visited the southernmost point of Canada reachable by road at Ontario’s Point Pelee National Park, and the easternmost point at Cape Spear National Historic Site in Newfoundland. This trip would see us reach Canada’s westernmost and northernmost mainland points as well. Few Canadians have done that, and even fewer can lay claim to completing the entire Parks Canada Xplorers program. It would be a heck of an achievement.

We landed in Edmonton ready to face whatever might lie ahead. What we didn’t know was how much this trip would teach us about bravery, trust, resilience, and how much we’re capable of — and about this spectacular and diverse country we call home.

A 2025 Toyota 4Runner Limited for towing

Since our route would involve some very rough and remote northern roads — including the Dempster Highway, Canada’s only mainland road that goes north of the Arctic Circle — I knew we’d need a vehicle that was up to the task.

I also decided from the outset that we’d need a travel trailer. If I’m driving all the way to the Arctic Ocean with a teenager, I figured, I’ll need to bring my own bathroom. (If you know, you know.)

This is how we found ourselves on our way to Hitch House in Edmonton to pick up a 2025 Toyota 4Runner Limited and a 19-foot trailer from Escape Trailers, a travel trailer manufacturer based in Chilliwack, B.C.

The sixth-generation 4Runner was built for exactly this sort of drive. It’s also the first 4Runner ever to ship with a factory-installed trailer brake controller, which is very handy given the towing aspect. The Escape Trailer is molded from seamless pieces of fibreglass, which prevents leaks and makes it tough enough to “last for generations,” according to the company. For this drive, we couldn’t have asked for a better combination.

I researched this trip for months, and I was confident I’d thought of a way out of every possible scenario. Still, I wondered exactly what I was signing us up for as we sat in the Uber leaving the airport. I closed my eyes and asked my dad to give me some kind of sign he’d be looking out for us along the way.

When we walked through the front door at Hitch House, I immediately recognized the song on the radio. It was “Wish You Were Here” by Pink Floyd, the same song we’d played at Dad’s funeral. Signs don’t get much clearer than that, do they?

I wiped a tear and tried to relax my shoulders. In that moment, I chose to believe nothing would be thrown at us we couldn’t handle.

Heading north on the Alaska Highway

For the first two days of our drive, we headed north on the Alaska Highway from Dawson Creek, B.C. It covers nearly 900 kilometres, including a portion in the Northern Rocky Mountains, to meet the Yukon border.

From a road tripping perspective, the B.C. portion of the Alaska Highway was the most satisfying stretch of our entire 8,000-kilometre drive. The remote mountain scenery and abundant wildlife here are unlike anything we’ve seen or experienced anywhere else in Canada.

We stumbled by accident on Summit Lake Campground, a first-come-first-served campground in Stone Mountain Provincial Park with some of the most beautiful campsites I’ve ever seen. The next morning, we stopped for a soak at Liard River Hot Springs Provincial Park, an unspoiled natural hot spring located deep in a remote northern forest. We spotted black bears, deer, and moose, and we even slowed down at one point to let a herd of bison cross the highway. (This is what’s known as a northern traffic jam.)

By the time we reached the Yukon border, I was ready to rank this road among Canada’s top 10 scenic drives.

In the Far North, follow these fuel-related guidelines

There are three important guidelines to follow around fuel when driving in the Far North.

1. Never let your fuel level drop below half if you can help it.

2. Once you’re approaching that point, don’t drive past a gas station, even if you think you can make it to the next one. (You never know if the truck is running late.)

3. Carry at least one gas can, especially if you’re at all unsure about the distances between stations and your vehicle’s range.

I pushed through my own anxieties and filled a gas can before leaving Dawson Creek, which took care of the third rule. Following the other two rules turned out to be more challenging than I’d bargained for.

While the 4Runner Hybrid had plenty of power and was a dream to tow with in most respects, its 72-litre fuel tank and the Escape Trailer’s 3,150-pound dry weight combined for a fuel economy average of 18.3 litres per 100 kilometres. This meant we were averaging just 400 kilometres per fill and had to stop to refuel every 200 kilometres on average. I had scheduled some very long drive days, and this made them feel even longer.

We covered 2,000 kilometres in our first three days and rolled into Whitehorse completely drained. And yet, in a sense, this isolated yet vibrant city is where our journey truly began. With a visit to the S.S. Klondike National Historic Site to see the last steam-powered paddlewheel ship to sail on the Yukon River — including a successful stint in the site’s very cool escape room — we had six sites left to go.

The majestic mountains of Kluane National Park and Reserve

Kluane National Park and Reserve has three important features that set it apart. Canada’s tallest mountain, Mount Logan, lies within its boundaries. In combination with the surrounding Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in B.C. and two U.S. national parks in Alaska, Kluane protects the largest non-polar ice field in the world. And its farthest corner, deep within the Saint Elias Mountains, is the westernmost point of Canada.

That actual westernmost point itself is essentially unreachable. We made it to Haines Junction and stepped foot within the park, which to us means we checked another Canadian geographic extreme off our list.

We stayed for a night at the park’s Kathleen Lake campground. My daughter skipped stones over the glacial lake’s pale blue waters with King’s Throne Peak standing majestically in the background. At a campfire talk, park staff explained how Kluane’s plants and animals coexist in this delicate northern ecosystem. It didn’t take us long to conclude a single night is not nearly long enough to experience this unique and special place. It’s high on my list for a return visit.

Stepping back in time to the Klondike Gold Rush

At the end of the 530-kilometre drive north from Whitehorse along the Klondike Highway lies Dawson City, the famed site of the Klondike Gold Rush. Here, the Dawson Historical Complex National Historic Site stands as Parks Canada’s second-largest living national historic site and the only one integrated within an active municipality.

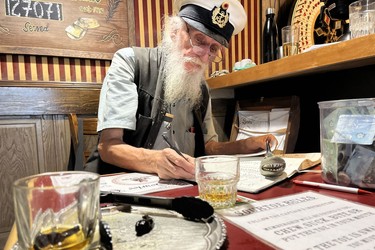

It takes some work to get here, but those intrepid travelers who make it are met with a fascinating history. The better-known side of Dawson City involves gold miners and their after-hours debauchery, such as the gambling hall and can-can show at Diamond Tooth Gertie’s. Dawson City is also famous for the Sourdough Saloon’s sourtoe cocktail. A shot of alcohol — typically Yukon Jack, of course — is served with a mummified human toe. If you drink it and let the toe touch your lips, you’ll get a souvenir certificate. (This tradition started in 1973, long after the Gold Rush ended.)

Today, though, there are opportunities to dig deeper. At Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site a few minutes outside of town, you can walk through one of the massive dredging machines that once extracted gold from the area’s riverbeds. And Parks Canada’s Red Surge, Red Tape program looks at how the Gold Rush affected the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, the Indigenous people who were displaced from their traditional hunting and fishing territory by it for more than a century.

We left Dawson City with two more Xplorers medallions and my mandatory Sourtoe Cocktail Club certificate. But we also left with something unexpected and much more valuable: a well-rounded perspective on a defining moment in the Yukon’s history.

The notorious Dempster Highway: to go or not to go?

Whether we’d make the trip up the Dempster Highway was a game-time decision.

It was also the talk of the campground in Dawson City: who had been, how each drive had gone, and who was scuttling their plans after hearing the horror stories.

This road’s reputation depends entirely on who you ask about it. Locals will tell you it’s just another gravel road. People who have seen its worst will tell you it’s one of the most challenging roads on the planet.

Either way, it’s roughly 900 kilometres of gravel and rock with no emergency or medical services at all for roughly half that distance. Help takes a very long time to arrive, if it ever does at all. If anything happens, you need to be ready to fend for yourself.

I’d researched and planned this trip for months, and I was convinced we couldn’t possibly be more prepared. We had a full spare for the 4Runner and a full spare for the Escape Trailer. I’d brought a tire inflator kit, spare tools, a full-size first aid kit, two full 25-litre jerry cans, a bottle jack, and more food and water than we could ever possibly need. Garmin provided an InReach Messenger Plus for us to review, which meant I’d be able to use satellite texting to stay in touch with loved ones and call for help if needed while we were outside mobile service range.

Still, I had some doubts. The first stretch from the start of the highway to Eagle Plains, the only service station on the Yukon section, is 368 kilometres. That was pushing the limits of the 4Runner’s range, and even two gas cans might not be enough fuel to get us to Fort McPherson if Eagle Plains was out. Plus, we’d watched a lot of people roll back into Dawson with flat tires. What if we ended up with one and I’d forgotten some critical piece to change it? Or worse?

My daughter and I had a long talk about it. We both knew the risks. We also knew getting to Tuktoyaktuk and the Arctic Ocean was one of the main goals of this trip.

Together, we decided to give it a go. We passed the sign marking the start of the highway, crossed the little blue bridge, and started our journey north.

Things fall apart — literally

The first hundred kilometres or so lulled me into a false sense of security. Through the Yukon’s Tombstone Territorial Park, the road is maintained and in decent shape. The rugged mountains and untouched landscapes are breathtaking. We saw a mother and baby moose wading in a lake. It dawned on us there are probably enormous swaths of land here that humans have never touched. It reminds you of how vast this country really is and makes you feel small very quickly.

Our first stop was at Engineer Creek Campground for lunch. By this point, the road was getting rough enough that it was starting to rattle us. As we made a quick bite to eat, we noticed the top hinge on the bathroom door had snapped in half. The other two hinges were supporting its weight fine, so we laughed about maybe having to use a bathroom without a door and continued on our way.

Past Engineer Creek, road conditions took a nosedive. Gravel gave way to exposed sections of uneven and jagged shale. The truck and trailer shuddered and rattled violently. In some sections, I was driving as slowly as 20 km/h just to keep the shaking manageable.

We just barely made it to Eagle Plains on fuel with 30 kilometres worth to spare. (And there was fuel available, thank goodness, which isn’t always a guarantee.) With that worry tended to, I decided to check on the trailer.

I opened the door to find another door leaning against it. The bottom hinge on the bathroom door had also snapped, and the middle hinge had popped right off under the strain. Fortunately, the entire thing fit into the storage compartment under the trailer’s double bed. (It must have looked very strange to see me standing in a parking lot in the middle of nowhere shoving a full-height door into the side of a trailer.)

Our next discovery? The rattling had caused an entire carton of eggs to shatter in the carton, leaving a goopy mess all over the bottom of our fridge. I used a full roll of paper towels cleaning it up and had to throw out a bunch of our fresh food. (Hot tip: if you’re going up the Dempster, don’t take eggs.)

Our plan for that first day was to make it as far as Fort McPherson, where we’d have access to a free unserviced campsite and mobile service. We pressed onward, crawling our way to the Arctic Circle. By this point, the trailer was full of dust, a bolt from the range cover had shaken itself loose and gone missing, our water tank had sprung a leak, pop cans were leaving skid marks on the shelves in the fridge, and our dish soap was emulsifying in the bottle.

My daughter admired the Arctic Circle marker while I stewed in self-doubt. I spotted a local with a Northwest Territories licence plate and asked her tentatively whether the road is equally bad the entire way. She said from the Northwest Territories border, just another 60 kilometres up the road, the conditions get much better.

She was right, though by that point the damage had been done, as the saying goes. We finally pulled into our campsite in Fort McPherson at about 11:30 p.m., hours later than I was expecting. I sat in the trailer with my head in my hands for a good half hour before I could even begin to think.

A sleepless night

That night, I hardly slept.

I’d only allotted four days for the drive from Dawson City to Tuktoyaktuk and back. This is not nearly enough time. An extra day for driving and one to two more to leave room for delays is all but essential.

By morning, I managed to convince myself I hadn’t planned this out properly at all and decided we should turn back. I’d already drafted the paragraph for this section in my head admitting I’d been defeated and run back to Dawson with my tail between my legs.

Two things kept me going.

One was my partner, Jay. I texted him that morning to talk through everything that had happened. He’s usually even more conservative than me, so I fully expected him to agree and tell me to get my behind back to Dawson. But he didn’t. Instead, he pointed out everything that had gone wrong to that point was cosmetic and easily fixable. We were only 340 kilometres away from Tuktoyaktuk, and he insisted we keep going. This wasn’t the response I was expecting from him at all, and it stopped me in my tracks.

The other was my daughter. “We’re so close,” she said when I told her I was thinking of turning around. “I think we should keep going.”

I had a rethink. Sure, more things could go wrong. But with the support of my closest people, for once in my life I thought to myself: what if they go right?

I gathered up all my resolve, put on my big girl pants, and pointed the 4Runner and trailer northbound.

A nightless sleep

The drive from Fort McPherson to Inuvik was a relative dream. There’s even a short paved stretch of highway between the Inuvik airport and the townsite, which provided a brief respite. But we still had the northernmost section of highway to go — technically this is a separate road called the Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk Highway, though most people refer to it as part of the Dempster — and I’d heard it was nearly as rough as the road around Eagle Plains.

“It’s just a road,” the manager at the Western Arctic Regional Visitor Centre in Inuvik said with a shrug when I inquired. (She also offered a gas coupon and some great information about attractions in the surrounding area, making this a very worthwhile stop.)

There were some rattling stretches on the ITH, too, and adventure motorbike riders tend to struggle most on this section due to the deep and loose gravel. But I was starting to get more comfortable — at least, until a truck going in the opposite direction started blaring its horn at me. I glanced at the rearview mirror.

“What the… we’re dragging something!” I said out loud.

That was our sewer hose, which had shredded down to a metal spring and was trailing along about 20 feet behind us. The caps for the storage tube, I presume, are still at the side of the highway somewhere north of Inuvik. Fortunately, this particular hose was unused and came in two parts, one of which was still intact. Into the storage bin the whole mess went.

I laughed my way through it. At this point, what else was there to do? We’d passed the tree line and were driving through open tundra surrounded by the Husky Lakes and dozens of brackish Arctic basins. In that moment, experiencing this rare and otherworldly landscape felt far more important.

And then came a cry from the back seat: “I see it!”

A cluster of colourful buildings on the horizon. Tuktoyaktuk. We made it!

Just before the edge of town, there’s a small pullout where the Pingo Canadian Landmark is visible. A pingo is a conical hill found only in permafrost, formed when ice gets trapped below the ground and forced it upward. My daughter was disappointed. “They’re just hills,” she declared. One day, she might come to appreciate that very few people can say they’ve seen these unusual formations for themselves.

We pulled into Tuk and grabbed a campsite for the night right on the shoreline. My daughter mailed a letter at the post office inside the Northern Store — yes, Canada Post really is everywhere — and we dipped our toes in the Arctic Ocean. A pair of musicians from Alberta and Newfoundland played a set on a stage in front of the Arctic Ocean sign. The sun didn’t set until 1:42 a.m. on this late July night, and it rose again three hours later.

Our time in Tuktoyaktuk was one of the most memorable nights of my life.

On the road back, we find kindness and community

The return drive was mostly without incident. I started to get more comfortable with the 4Runner’s shudder, a common trait in rugged body-on-frame trucks, and stopped cringing every time I opened the trailer door during rest stops. The two ferries over the Peel and Mackenzie rivers can sometimes shut down and cause delays, but we got over both right away. Things were going well.

Until 20 kilometres north of Eagle Plains when — ding! There goes the tire pressure monitor.

Now, if you’re going to get a flat tire on the Dempster — and as we’ve established, consider it inevitable — this is the best possible scenario. The leak in the 4Runner’s right rear tire was slow enough that I managed to nurse our entire rig into the campground at the Eagle Plains Hotel, which is where we’d planned to spend the night anyway. This way, I could take my time with it instead of struggling at the side of the road.

I expressed out loud that I wasn’t looking forward to changing a tire on my own for the first time. “I can do it, Mom,” my daughter replied. This is true. When she’s not on the road with me, she spends her summer weekends at the racetrack as part of her dad’s pit crew. She’s probably better qualified for the task than I am.

We grabbed a bite to eat at the hotel’s restaurant — cooking a meal was the last thing I felt like dealing with in that moment — and went back to the campsite to get to work.

A couple in a red pickup with a bed camper was parked beside us. The woman was the first to come over and say hello. Her name, I’d learn later, is Laura.

“You know your water tank is leaking?” she asked.

“Yep,” I replied. “And it looks like a rock cracked my black water plunger case, so I need to deal with that, too.”

“And you know you’ve got a flat?”

“Sure do! That’s third on my list.”

“That sucks,” she sighed. “Let us know if we can help. We’re pretty well equipped.”

I’m not typically one to accept offers of help. But after one sober look at my situation, it took me about 90 seconds to take her up on it.

The water leak was slow, but I was having a hard time diagnosing it. Steve, Laura’s husband, is a kind Brit with sharp blue eyes and a witty sense of humour. He saw me struggling and came over to take a look. It turns out a rock had hit the spigot on the water tank and put a sizeable crack in it. He threw some zip ties around it to stem the leak until we could find a replacement.

I tidied up and taped the plunger cover and then started puzzling my way through the tire change. Steve stepped in to help here, too. It turns out I couldn’t have asked for better neighbours: before a devastating motorbike crash derailed his career, Steve had been a mechanic for 30 years. He and Laura now live on the road full-time. They had a complete kit at their disposal, including an air compressor and a digital torque wrench.

Steve also overheard that my daughter wanted to help change the tire. “Right,” he said to her. “Let’s get on with it.”

Next thing I knew, she and Steve were leafing through the owner’s manual, dropping the spare from underneath the 4Runner, and getting the truck jacked up. She was learning resilience and self-sufficiency; I was learning to trust the kindness of strangers.

Once the job was done, I asked how I could possibly repay them. I offered food, a can of gas, and pretty well everything else I had. Both Steve and Laura refused and insisted that I just pay it forward. I later came to learn Steve had already changed a tire on his own truck that day and helped two other people change theirs, pushing through the chronic pain from his crash injuries to do anything he could for those around him.

We continued chatting as the evening wound down, and I finally got around to telling Steve what I do for a living.

“Really?” he quipped with a glint in his eye. “Shouldn’t you know how to do this stuff, then?”

I absolutely should. And now I do, and so does my daughter. Steve and Laura are honest-to-goodness road angels who turned a grim situation into an immensely positive one. I’m so grateful to have met them in precisely the right place and the right time.

The next day, we pay it forward

In the morning, I had the flat tire patched and reinflated by the Eagle Plains shop so we could use it as a backup, just in case. We then settled in for the final run toward Dawson.

We trundled down the road for a hundred kilometres or so before we came across a familiar sight: a red pickup with a bed camper, parked in a pullout with its hood up. I spotted Laura standing beside it and immediately ground the 4Runner to a halt.

Steve and Laura had decided that morning not to continue up to Tuk and instead turned back toward Dawson. They’d picked up two more flats since they’d left, and the patches in the last one weren’t taking. They had to stop every 50 kilometres or so to reinflate the tire so they could keep going.

I told them I’d trail them to Dawson and stop with them when they needed to. That way, if the tire fully failed, I could give one of them a ride into town to get a new one.

“You don’t have to do that,” Steve replied.

I roundly ignored him. How could I possibly carry on down the road on my own after everything they’d done for us?

After a couple more stops, the leak became more persistent and no amount of patching and inflating was helping. Suddenly, I remembered the tire inflator kit I’d bought, the kind that squirts sticky gunk into the tire to seal leaks from the inside. It was the wrong can size for their Super Duty’s tires, but I offered it up as a last-ditch option.

With the gunk inside and the tire re-inflated, Steve and Laura took off ahead of me. They texted me later to let me know the inflator kit sealed the tire well enough to get them safely back to Dawson, and that they’d taken comfort in knowing I was behind them if needed. I never expected I’d get to repay their kindness so quickly.

Our last 200 kilometres threw another minor wrench at us: a driving rain that turned the road’s dust and gravel into a slick mud. I counted off each kilometre marker like a mantra. I’ve never been so grateful to see a little blue bridge in my life.

We shouted in victory as we pulled into the gas station at Dempster Corner, again with 30 kilometres to spare after filling up at Eagle Plains. I turned around to give the Dempster Highway one last withering look — and there, across the entire horizon, we were greeted with a brilliant double rainbow.

Thanks for looking out for us, Dad. I’m really proud of us, too.

A note about travel trailers on the Dempster Highway

At no point on this drive was I concerned about the 4Runner. It’s rugged, durable, and built for exactly these kinds of challenges.

I was concerned about the Escape Trailer, though, only because I wasn’t as familiar with it. This description makes it sound like it didn’t fare all that well, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. The things that went wrong were all cheap and easy fixes, and they would have happened with just about any trailer short of a dedicated overlander. We had almost everything sorted out by the time we left Whitehorse for the second time, and for less than $100.

The Escape’s critical systems, on the other hand, were rock solid and never failed us once. And unlike most trailers where a minor speed bump will cause the cabinets to fly open, every cupboard stayed closed for our entire trip up the Dempster Highway. I was genuinely impressed with how well it held up, and I really do believe Escape’s rigid fibreglass construction contributed to its relative success here.

That said, Dempster veterans will tell you not to take a travel trailer on the highway at all — something I learned too late — and this is sound advice. Most people choose to leave their trailers at the campgrounds in Dawson and stay in hotels while headed north. Rooftop tents and truck bed campers are also very popular in this part of the world. And my concerns about needing our own bathroom were unfounded: there are plenty of rest stops with pit toilets along the way.

If you decide to try this epic journey, learn from my experience and leave your travel trailer behind.

Continuing on the Great Northern Circle Route

Northern British Columbia’s Great Northern Circle Route starts in Dawson Creek and follows the Alaska Highway northbound to just west of Watson Lake, where it returns southbound on Highway 37. That happened to be our best path to Prince Rupert, so we ended up following much of the route, albeit in a fragmented fashion.

Highway 37 feels much more remote than the Alaska Highway. There’s no mobile service anywhere along the route. Visitor services are sporadic in some sections and non-existent in others, particularly the northernmost 250 kilometres where it’s nothing but a ribbon of asphalt in the wilderness. If you want to feel like you’ve run off to the mountains and left all of civilization behind, this is the place to do it.

We were just grateful the road was paved and in relatively good condition. It was easy to sit back and enjoy the scenery as we met up with the Trans-Canada Highway and headed west to Prince Rupert.

From here, the plan was to take the seven-hour ferry across to Haida Gwaii and then join a boat tour to visit Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site. Unfortunately, this went completely sideways: our tour was cancelled due to rain and high winds. The one full day we had on the islands happened to be B.C. Day, which meant absolutely everything was closed, including the Haida Heritage Centre in Skidegate.

We walked along the rocky beaches, went to Mile 0 of the Yellowhead Highway, took a look at Balance Rock, and otherwise hid from the rain in the trailer and watched movies instead.

The closest we got to Gwaii Haanas was a view of its northern extremes from the ferry. We left with the Xplorers tag anyway, along with a promise to learn more about the Haida people and their culture on our own — and to return at the earliest opportunity.

A mission, complete

As the Yellowhead Highway leaves Prince Rupert to head east, it transitions from towering mountains and ocean inlets to the flat lands of the Nechako Plateau. It’s here in Fort St. James, on the shores of Stuart Lake, where our Parks Canada Xplorers journey reached its finale.

Fort St. James National Historic Site is a former fur trading post dating back to the 1800s. Some of the site’s buildings are original and located exactly where they were first built. By walking through the fort and interacting with the interpreters in period costume, you’ll learn about how the fur trade operated, the Voyageurs and Indigenous peoples who passed through, and how a history of horse racing evolved into the fort’s top present-day attraction, the daily chicken races.

That’s right: after visiting more than 100 national parks and national historic sites across Canada, seeing glorious landscapes and learning an encyclopedia’s worth of details about our nation’s past, the very last Parks Canada Xplorers activity my daughter and I did together was betting on chicken races. Go figure.

We left that day, clutching the final medallion to complete our collection, with a mix of elation and emptiness. A silent question hung in the air: now what?

“I hope we’ll still go on road trips together,” my daughter said. “There’s still a lot of Canada for us to see. And we can start traveling to other places, too!”

If this last decade of childhood adventures has sparked a lifetime of curiosity about and exploration of the world, then every single kilometre has been worth it. Mission accomplished.

And if I’ve learned one thing from this entire experience, it’s that the Xplorers program does a lot more than educate kids. I now know far more than I ever expected to learn about this amazing country we call home, which I now view with very different eyes. But I also learned just how important travel is for the soul — and that, with a little determination, we’re all capable of far more than we really know.

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.