Canadian author Linden MacIntyre explores dark and violent period in history

Article content

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

It was a clearly expressed mandate — “the stamping out of terrorism by secret murder.”

That’s how one highly-placed observer saw the situation more than a century ago when the Irish War of Independence was raging and the British government was determined to suppress it by whatever means possible.

So if it was necessary to counter civil unrest and domestic terrorism with indiscriminate brutality and state-sanctioned killings — well, it was for the good of the empire, wasn’t it?

Award-winning Canadian writer Linden MacIntyre was drawn to these violent times because of the abiding mystery surrounding the man in charge of the British response — a distinguished First World War hero so tarnished by his two years in Ireland, and so vulnerable to assassination in the aftermath, that he spent the last 40 years of his life in exile — in Newfoundland.

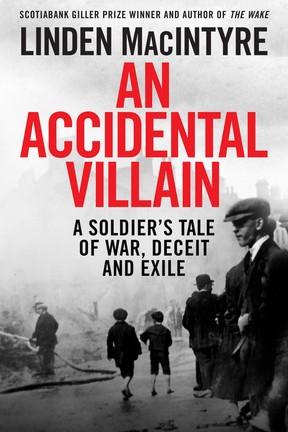

With his fascinating new book, An Accidental Villain, MacIntyre has sought to untangle the enigma of Major General Hugh Tudor, an officer prepared to abandon honour and principle, qualities instilled in him by his military background, and do the bidding of his friend Winston Churchill who had thrust him into a soul-shrivelling task. Where, for example, was Tudor’s moral compass in November, 1920, when, as head of the Irish Police Force, he would countenance an event like Bloody Sunday which saw his men indiscriminately slaughter innocent Irish football fans?

An Accidental Villain

Linden MacIntyre

Random House

“What I hope readers take away is the realization that it’s possible for people to suppress their natural moral sensibility, their natural sense of humanity, in order to serve the strategies and ambitions of powerful and ruthless leaders,” MacIntyre tells Postmedia.

As a former member of CBC Television’s Fifth Estate team, MacIntyre is well-schooled in investigative journalism. Sir Hugh Tudor, however, posed a particularly daunting challenge. Yes, there were early wartime diaries “but they were not especially well-written — to put it mildly they lack drama and poetry and are just a kind of dry narration.”

The diaries didn’t help MacIntyre enter the elusive mind of the man who wrote them. And Ireland was even more frustrating: “He wrote nothing about himself.” Researches in London also led to dead ends, leaving MacIntyre astonished that some archival resources didn’t even contain a designated Tudor file.

‘What I had to do instead was go through the records of people he was most identified with. There you find an occasional letter or memorandum but virtually nothing about the man’s character or inner thoughts.”

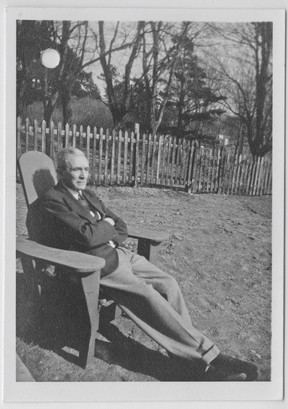

For MacIntyre, it was like “following a shadow.” The crucial Irish period was one obstacle, but there were further frustrations — for example in seeking justification for Tudor’s inexplicable attempt to terminate his marriage. Even the decades of quiet exile in Newfoundland proved elusive: yes, Tudor entered the fisheries business, yes he became an important enough figure in the St. John’s community to receive invitations to the governor’s mansion — but what was he really like? Tudor died in 1965 at the age of 94, and MacIntyre was able to track a few people who had known him in his final years, but the enigma persisted.

So what compelled MacIntyre to write a book? The answer constitutes a fascinating story in itself. He had been reading an academic paper about the top-secret summit meeting between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt off the coast of Newfoundland in 1941. The paper included the contents of a cable to Newfoundland’s governor from Churchill, a cable which among other things expressed the hope that while there he might be able to meet his old friend Hugh Tudor.

That brief phrase triggered MacIntyre’s curiosity. Who on earth was this man, Hugh Tudor?

“I did some research and discovered he had been the head of the Irish police during the War of Independence and that he was responsible for this crowd of thugs who wore police uniforms and were known as the Black and Tans. So now here’s their boss, the guy who was their leader, living in St. John’s … keeping his head down and surviving.”

MacIntyre’s vivid but balanced chapters on the Irish violence acknowledge the horrors committed on both sides, but for him a consuming question remains. How and why did Hugh Tudor — by all accounts a soldier of courage, honour, and integrity — lose his moral compass in so brutally responding to Ireland’s fight for independence?

“It’s always difficult to find the origins of a moral blindness,” MacIntyre says. “He wasn’t greedy, he had no great ambitions, and he wasn’t doing this for any kind of reward although he got a knighthood out of it.”

Indeed, Tudor had no strong opinions about Ireland when he went there, but his attitude hardened. “The Irish started killing he people he cared about, and I think that helps explain the dropping of whatever moral restraints he might have had: if that’s the way you want to play it, I’m going to play it as dirty as possible.”

“It’s always difficult to find the origins of a moral blindness.”

Most crucial however was his devotion to his old wartime comrade Winston Churchill who, as a member of the cabinet of Prime Minister David Lloyd George, summoned him back to duty. “Tudor saw in Churchill the leader he was willing to die for. So when Churchill needed someone he could trust to take charge of the campaign against the Irish independence movement, he personally selected General Tudor.”

This new book carries the subtitle “A Soldier’s Tale of Deceit and Exile.”

Why deceit? “Tudor was deceived by Churchill and Lloyd George,” MacIntyre says bluntly.

The two British leaders wanted to distance themselves from accountability for what happened, but they saw Tudor as an instrument for creating a sideshow that “would terrorize the Irish people into submission.

“They never really brought Tudor honestly into the picture because they couldn’t. But they kept telling him he was a great warrior who was doing a remarkable job for the British Empire.”

So was this ‘great warrior’ only obeying orders?

MacIntyre’s response: “That’s the most cruel and truthful bottom line to all this.”

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.