Author Maria Reva's return to Ukraine inspired her to complete novel

Article content

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

In 2023, Maria Reva and her sister were on a train hurtling through a Ukrainian night toward the battle-scarred city of Kherson. They were hoping to reach their grandfather, still there in the midst of carnage. It was crisis time for Reva in more ways than one. The novel she had started to write back in Canada was in jeopardy: what she had originally envisaged as a lighthearted romp satirizing Ukraine’s controversial “romance” tours had been upended by Russian aggression.

“I initially felt I had two choices,” the award-winning Canadian writer says now. “I could keep writing the novel as though nothing happened in real time. Or I could give up on it.”

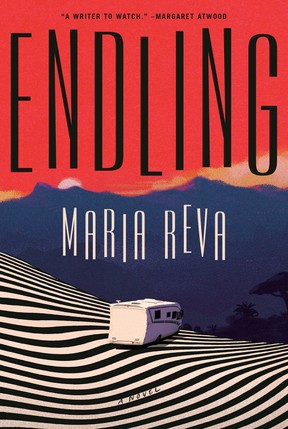

Ultimately, she didn’t give up. That return to Ukraine helped her find a way back in, and her debut novel, Endling, has now been published to international acclaim. Typical is the verdict of revered American novelist Percival Everett: “I love works that are smarter than I am, and this is one.” He’s talking about a daring, genre-bending achievement in which Reva herself becomes a recurring presence in the course of a fast-paced narrative.

Endling

Maria Reva

Knopf Canada

“I gave up on it multiple times,” she tells Postmedia from her home on Canada’s West Coast. “I honestly did not envisage any future for it beyond finishing it.”

In the midst of this struggle came the need to return to the embattled country of her birth. Reva was seven when she and her family emigrated to Canada in 1997. She had been back many time since — “but I had a sense of terror when I thought of going to Ukraine this time.” Still, she would adjust to the psychology of a country under siege. Once there, as the sisters moved eastward in the hope of reaching their grandfather, “the sense of danger became more and more normalized.” Yet danger was definitely present.

“On the train during the night, the conductor asked us to keep the blinds down so that we would not emit any light because trains had become a target for the Russians. The way that my sister and I thought of it was that we were in a closed moving coffin.”

The moment came when they could go no further. They would not reach the grandfather they loved.

“It was very difficult accepting limitations on what I was capable of,” Reva says sombrely. “I think that’s why my fiction allows me the fantasy of going where I could not.” So a grandfather figure does play a seminal role in the novel she was able to complete.

Reva’s lighter side surfaced on late-night television a few weeks ago with her cheerfully discussing the sex life of snails with NBC host Seth Meyers. She might have seemed light-years away from the horrors of Ukraine but in fact she was talking about the very same book, Endling, that had confronted her with so many challenges.

But snails? Really? Well, an endangered specimen named Lefty turns out to be the key player in a high-intensity scene near the end of the book. Besides, in this author’s imaginative world, why shouldn’t the fate of a mollusk symbolize the eternal conflict between darkness and light?

Early in the novel, we meet a dedicated scientist named Yeva whose mission in life is to track down rare species of snail and save them from extinction. She helps finance her quest by working in Ukraine’s romance tour industry — dating foreign bachelors who have signed up for these ventures in the hope of acquiring a beautiful, pliable fantasy bride. Desperate for money, she finally allows her travelling RV lab to be used in a bizarre plot concocted by feminist militants to discredit the tours — and then the hell of war erupts.

“The novel was intended to be a comedic kidnapping caper, a kind of anti-romance-tour book,” Reva explains. “That was what I was setting out to write about — that and snail conservation work in the Ukraine.” She wanted to utilize “light humour” as a means of examining contemporary issues. The Russian invasion landed her in a creative mire

“I finally realized the only way I could keep writing the novel was to pour into it all the ambivalence I was feeling, the questions I had about myself as a writer and the role I then had as an observer of the war from abroad.”

The ambivalence stands revealed on page 109 of the finished novel when Reva makes her first personal entry into its pages and shares with the reader a message to her agent: “I was writing about a so-called invasion of Western bachelors to Ukraine and then an actual invasion happened. To continue now seems unforgivable.” But she did continue — and there would be more personal interventions in the book’s narrative.

She’s not the first writer to rework fictional convention. Centuries ago, Laurence Sterne did it with Tristram Shandy, and more recently John Fowles, Ian McEwan and George Saunders have shown similar boldness. But here, Reva was attempting a multilayered meshing of tone and mood but, equally dangerous, of form and structure — while also ensuring the presence in her pages of living, breathing, fallible human beings.

“I was very apprehensive,” she admits with a laugh. “I didn’t know if i could pull it off. I knew that I might scare some readers.” But then the stylistically audacious Oscar-winning film, Everything Everywhere All At Once, came along and she felt safer. “That’s what made me confident enough to wrote this book in the way that I needed to write it.”

Furthermore, although dealing with the darkest of subject matter, she did not stifle her innate gift for humour. She retains the sparkling satire of her early chapters lampooning the marriage tour industry, and later in the book offers the comedy of menace in satirizing to cutting effect what happens when a crew of Russian propagandists arrives to shoot a bogus documentary about the gratitude ordinary Ukrainians feel toward their Russian liberators.

“Humour has a really long tradition in Ukraine as a way to deal with difficult circumstances,” Reva says. “It’s a survival mechanism. If somebody can laugh at something bad, they can rise above it — they can take away its power over them.”

As for the book’s title — well an “endling” is the last known member of a species on the verge of becoming extinct, but its use here can have wider implications. If readers come away with a sense of hope, which is Reva’s fervent wish, Lefty the snail will have something to do with it.

“I’m not a religious person so I haven’t found a solution for myself in dealing with the chaos and utter unknowability of the universe,” Reva says. “But do suspect that we tell ourselves stories to cover the face of chaos and imbue it with meaning. That ultimately is what the book about. What stories do we tell ourselves in order to feel secure?”

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.